Ver no TensorFlow.org Ver no TensorFlow.org |  Executar no Google Colab Executar no Google Colab |  Ver fonte no GitHub Ver fonte no GitHub |  Baixar caderno Baixar caderno |

Neste Colab, exploramos alguns dos recursos fundamentais da Probabilidade do TensorFlow.

Dependências e pré-requisitos

Importar

from pprint import pprint

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

import tensorflow.compat.v2 as tf

tf.enable_v2_behavior()

import tensorflow_probability as tfp

sns.reset_defaults()

sns.set_context(context='talk',font_scale=0.7)

plt.rcParams['image.cmap'] = 'viridis'

%matplotlib inline

tfd = tfp.distributions

tfb = tfp.bijectors

Útil

def print_subclasses_from_module(module, base_class, maxwidth=80):

import functools, inspect, sys

subclasses = [name for name, obj in inspect.getmembers(module)

if inspect.isclass(obj) and issubclass(obj, base_class)]

def red(acc, x):

if not acc or len(acc[-1]) + len(x) + 2 > maxwidth:

acc.append(x)

else:

acc[-1] += ", " + x

return acc

print('\n'.join(functools.reduce(red, subclasses, [])))

Contorno

- TensorFlow

- Probabilidade do TensorFlow

- Distribuições

- Bijetores

- MCMC

- ...e mais!

Preâmbulo: TensorFlow

TensorFlow é uma biblioteca de computação científica.

Suporta

- muitas operações matemáticas

- computação vetorizada eficiente

- aceleração de hardware fácil

- diferenciação automática

Vetorização

- A vetorização torna as coisas mais rápidas!

- Também significa que pensamos muito sobre formas

mats = tf.random.uniform(shape=[1000, 10, 10])

vecs = tf.random.uniform(shape=[1000, 10, 1])

def for_loop_solve():

return np.array(

[tf.linalg.solve(mats[i, ...], vecs[i, ...]) for i in range(1000)])

def vectorized_solve():

return tf.linalg.solve(mats, vecs)

# Vectorization for the win!

%timeit for_loop_solve()

%timeit vectorized_solve()

1 loops, best of 3: 2 s per loop 1000 loops, best of 3: 653 µs per loop

Aceleraçao do hardware

# Code can run seamlessly on a GPU, just change Colab runtime type

# in the 'Runtime' menu.

if tf.test.gpu_device_name() == '/device:GPU:0':

print("Using a GPU")

else:

print("Using a CPU")

Using a CPU

Diferenciação Automática

a = tf.constant(np.pi)

b = tf.constant(np.e)

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

tape.watch([a, b])

c = .5 * (a**2 + b**2)

grads = tape.gradient(c, [a, b])

print(grads[0])

print(grads[1])

tf.Tensor(3.1415927, shape=(), dtype=float32) tf.Tensor(2.7182817, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Probabilidade do TensorFlow

TensorFlow Probability é uma biblioteca para raciocínio probabilístico e análise estatística no TensorFlow.

Apoiamos modelagem, inferência e críticas através da composição de componentes modulares de baixo nível.

Blocos de construção de baixo nível

- Distribuições

- Bijetores

Construções de alto (er) nível

- Cadeia de Markov Monte Carlo

- Camadas Probabilísticas

- Séries Temporais Estruturais

- Modelos Lineares Generalizados

- Otimizadores

Distribuições

Um tfp.distributions.Distribution é uma classe com dois métodos principais: sample e log_prob .

A TFP tem muitas distribuições!

print_subclasses_from_module(tfp.distributions, tfp.distributions.Distribution)

Autoregressive, BatchReshape, Bates, Bernoulli, Beta, BetaBinomial, Binomial Blockwise, Categorical, Cauchy, Chi, Chi2, CholeskyLKJ, ContinuousBernoulli Deterministic, Dirichlet, DirichletMultinomial, Distribution, DoublesidedMaxwell Empirical, ExpGamma, ExpRelaxedOneHotCategorical, Exponential, FiniteDiscrete Gamma, GammaGamma, GaussianProcess, GaussianProcessRegressionModel GeneralizedNormal, GeneralizedPareto, Geometric, Gumbel, HalfCauchy, HalfNormal HalfStudentT, HiddenMarkovModel, Horseshoe, Independent, InverseGamma InverseGaussian, JohnsonSU, JointDistribution, JointDistributionCoroutine JointDistributionCoroutineAutoBatched, JointDistributionNamed JointDistributionNamedAutoBatched, JointDistributionSequential JointDistributionSequentialAutoBatched, Kumaraswamy, LKJ, Laplace LinearGaussianStateSpaceModel, LogLogistic, LogNormal, Logistic, LogitNormal Mixture, MixtureSameFamily, Moyal, Multinomial, MultivariateNormalDiag MultivariateNormalDiagPlusLowRank, MultivariateNormalFullCovariance MultivariateNormalLinearOperator, MultivariateNormalTriL MultivariateStudentTLinearOperator, NegativeBinomial, Normal, OneHotCategorical OrderedLogistic, PERT, Pareto, PixelCNN, PlackettLuce, Poisson PoissonLogNormalQuadratureCompound, PowerSpherical, ProbitBernoulli QuantizedDistribution, RelaxedBernoulli, RelaxedOneHotCategorical, Sample SinhArcsinh, SphericalUniform, StudentT, StudentTProcess TransformedDistribution, Triangular, TruncatedCauchy, TruncatedNormal, Uniform VariationalGaussianProcess, VectorDeterministic, VonMises VonMisesFisher, Weibull, WishartLinearOperator, WishartTriL, Zipf

Um escalar-variada simples Distribution

# A standard normal

normal = tfd.Normal(loc=0., scale=1.)

print(normal)

tfp.distributions.Normal("Normal", batch_shape=[], event_shape=[], dtype=float32)

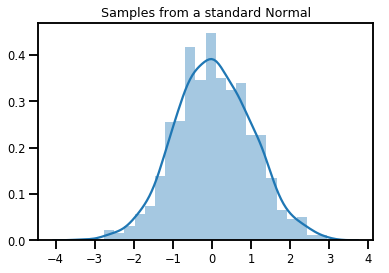

# Plot 1000 samples from a standard normal

samples = normal.sample(1000)

sns.distplot(samples)

plt.title("Samples from a standard Normal")

plt.show()

# Compute the log_prob of a point in the event space of `normal`

normal.log_prob(0.)

<tf.Tensor: shape=(), dtype=float32, numpy=-0.9189385>

# Compute the log_prob of a few points

normal.log_prob([-1., 0., 1.])

<tf.Tensor: shape=(3,), dtype=float32, numpy=array([-1.4189385, -0.9189385, -1.4189385], dtype=float32)>

Distribuições e formas

Numpy ndarrays e TensorFlow Tensors têm formas.

TensorFlow Probabilidade Distributions têm forma semântica - formas de partições que nós em pedaços semanticamente distintas, embora o mesmo pedaço de memória ( Tensor / ndarray ) é usado para toda a tudo.

- Forma de lote indica um conjunto de

Distributions com parâmetros distintos - Forma evento denota a forma de amostras da

Distribution.

Sempre colocamos formas de lote à "esquerda" e formas de evento à "direita".

Um lote de escalar-variada Distributions

Os lotes são como distribuições "vetorizadas": instâncias independentes cujos cálculos acontecem em paralelo.

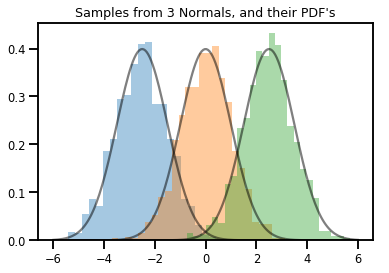

# Create a batch of 3 normals, and plot 1000 samples from each

normals = tfd.Normal([-2.5, 0., 2.5], 1.) # The scale parameter broadacasts!

print("Batch shape:", normals.batch_shape)

print("Event shape:", normals.event_shape)

Batch shape: (3,) Event shape: ()

# Samples' shapes go on the left!

samples = normals.sample(1000)

print("Shape of samples:", samples.shape)

Shape of samples: (1000, 3)

# Sample shapes can themselves be more complicated

print("Shape of samples:", normals.sample([10, 10, 10]).shape)

Shape of samples: (10, 10, 10, 3)

# A batch of normals gives a batch of log_probs.

print(normals.log_prob([-2.5, 0., 2.5]))

tf.Tensor([-0.9189385 -0.9189385 -0.9189385], shape=(3,), dtype=float32)

# The computation broadcasts, so a batch of normals applied to a scalar

# also gives a batch of log_probs.

print(normals.log_prob(0.))

tf.Tensor([-4.0439386 -0.9189385 -4.0439386], shape=(3,), dtype=float32)

# Normal numpy-like broadcasting rules apply!

xs = np.linspace(-6, 6, 200)

try:

normals.log_prob(xs)

except Exception as e:

print("TFP error:", e.message)

TFP error: Incompatible shapes: [200] vs. [3] [Op:SquaredDifference]

# That fails for the same reason this does:

try:

np.zeros(200) + np.zeros(3)

except Exception as e:

print("Numpy error:", e)

Numpy error: operands could not be broadcast together with shapes (200,) (3,)

# But this would work:

a = np.zeros([200, 1]) + np.zeros(3)

print("Broadcast shape:", a.shape)

Broadcast shape: (200, 3)

# And so will this!

xs = np.linspace(-6, 6, 200)[..., np.newaxis]

# => shape = [200, 1]

lps = normals.log_prob(xs)

print("Broadcast log_prob shape:", lps.shape)

Broadcast log_prob shape: (200, 3)

# Summarizing visually

for i in range(3):

sns.distplot(samples[:, i], kde=False, norm_hist=True)

plt.plot(np.tile(xs, 3), normals.prob(xs), c='k', alpha=.5)

plt.title("Samples from 3 Normals, and their PDF's")

plt.show()

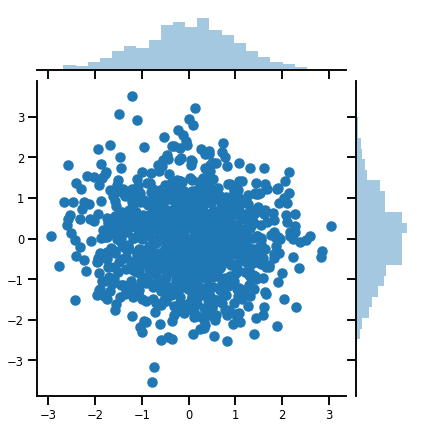

Um vector-variada Distribution

mvn = tfd.MultivariateNormalDiag(loc=[0., 0.], scale_diag = [1., 1.])

print("Batch shape:", mvn.batch_shape)

print("Event shape:", mvn.event_shape)

Batch shape: () Event shape: (2,)

samples = mvn.sample(1000)

print("Samples shape:", samples.shape)

Samples shape: (1000, 2)

g = sns.jointplot(samples[:, 0], samples[:, 1], kind='scatter')

plt.show()

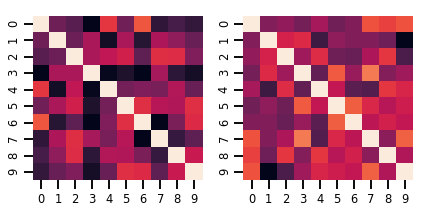

Uma matriz-variada Distribution

lkj = tfd.LKJ(dimension=10, concentration=[1.5, 3.0])

print("Batch shape: ", lkj.batch_shape)

print("Event shape: ", lkj.event_shape)

Batch shape: (2,) Event shape: (10, 10)

samples = lkj.sample()

print("Samples shape: ", samples.shape)

Samples shape: (2, 10, 10)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(6, 3))

sns.heatmap(samples[0, ...], ax=axes[0], cbar=False)

sns.heatmap(samples[1, ...], ax=axes[1], cbar=False)

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

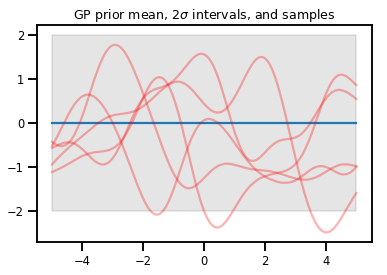

Processos Gaussianos

kernel = tfp.math.psd_kernels.ExponentiatedQuadratic()

xs = np.linspace(-5., 5., 200).reshape([-1, 1])

gp = tfd.GaussianProcess(kernel, index_points=xs)

print("Batch shape:", gp.batch_shape)

print("Event shape:", gp.event_shape)

Batch shape: () Event shape: (200,)

upper, lower = gp.mean() + [2 * gp.stddev(), -2 * gp.stddev()]

plt.plot(xs, gp.mean())

plt.fill_between(xs[..., 0], upper, lower, color='k', alpha=.1)

for _ in range(5):

plt.plot(xs, gp.sample(), c='r', alpha=.3)

plt.title(r"GP prior mean, $2\sigma$ intervals, and samples")

plt.show()

# *** Bonus question ***

# Why do so many of these functions lie outside the 95% intervals?

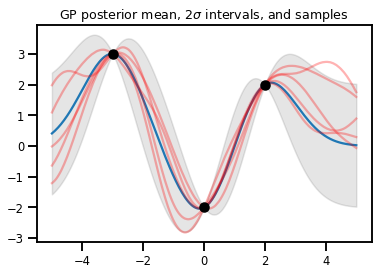

Regressão GP

# Suppose we have some observed data

obs_x = [[-3.], [0.], [2.]] # Shape 3x1 (3 1-D vectors)

obs_y = [3., -2., 2.] # Shape 3 (3 scalars)

gprm = tfd.GaussianProcessRegressionModel(kernel, xs, obs_x, obs_y)

upper, lower = gprm.mean() + [2 * gprm.stddev(), -2 * gprm.stddev()]

plt.plot(xs, gprm.mean())

plt.fill_between(xs[..., 0], upper, lower, color='k', alpha=.1)

for _ in range(5):

plt.plot(xs, gprm.sample(), c='r', alpha=.3)

plt.scatter(obs_x, obs_y, c='k', zorder=3)

plt.title(r"GP posterior mean, $2\sigma$ intervals, and samples")

plt.show()

Bijetores

Os bijetores representam funções suaves (principalmente) invertíveis. Eles podem ser usados para transformar distribuições, preservando a capacidade de obter amostras e calcular log_probs. Eles podem estar na tfp.bijectors módulo.

Cada bijetor implementa pelo menos 3 métodos:

-

forward, -

inverse, e - (pelo menos) um de

forward_log_det_jacobianeinverse_log_det_jacobian.

Com esses ingredientes, podemos transformar uma distribuição e ainda obter amostras e log probs do resultado!

Em matemática, um tanto descuidadamente

- \(X\) é uma variável aleatória com pdf \(p(x)\)

- \(g\) é uma função suave, invertível no espaço de \(X\)'s

- \(Y = g(X)\) é, uma variável aleatória transformada novo

- \(p(Y=y) = p(X=g^{-1}(y)) \cdot |\nabla g^{-1}(y)|\)

Cache

Os bijetores também armazenam em cache as computações de avanço e inverso e log-det-Jacobians, o que nos permite economizar a repetição de operações potencialmente muito caras!

print_subclasses_from_module(tfp.bijectors, tfp.bijectors.Bijector)

AbsoluteValue, Affine, AffineLinearOperator, AffineScalar, BatchNormalization Bijector, Blockwise, Chain, CholeskyOuterProduct, CholeskyToInvCholesky CorrelationCholesky, Cumsum, DiscreteCosineTransform, Exp, Expm1, FFJORD FillScaleTriL, FillTriangular, FrechetCDF, GeneralizedExtremeValueCDF GeneralizedPareto, GompertzCDF, GumbelCDF, Identity, Inline, Invert IteratedSigmoidCentered, KumaraswamyCDF, LambertWTail, Log, Log1p MaskedAutoregressiveFlow, MatrixInverseTriL, MatvecLU, MoyalCDF, NormalCDF Ordered, Pad, Permute, PowerTransform, RationalQuadraticSpline, RayleighCDF RealNVP, Reciprocal, Reshape, Scale, ScaleMatvecDiag, ScaleMatvecLU ScaleMatvecLinearOperator, ScaleMatvecTriL, ScaleTriL, Shift, ShiftedGompertzCDF Sigmoid, Sinh, SinhArcsinh, SoftClip, Softfloor, SoftmaxCentered, Softplus Softsign, Split, Square, Tanh, TransformDiagonal, Transpose, WeibullCDF

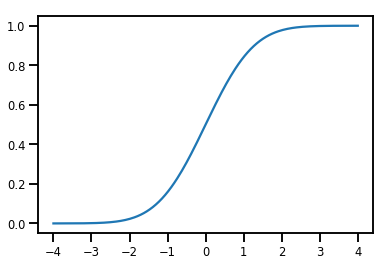

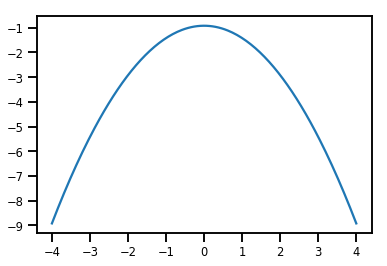

Um simples Bijector

normal_cdf = tfp.bijectors.NormalCDF()

xs = np.linspace(-4., 4., 200)

plt.plot(xs, normal_cdf.forward(xs))

plt.show()

plt.plot(xs, normal_cdf.forward_log_det_jacobian(xs, event_ndims=0))

plt.show()

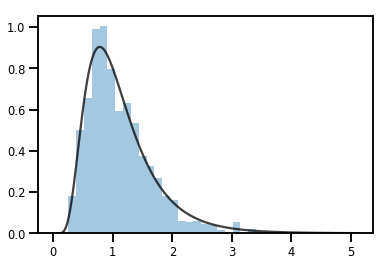

A Bijector transformar uma Distribution

exp_bijector = tfp.bijectors.Exp()

log_normal = exp_bijector(tfd.Normal(0., .5))

samples = log_normal.sample(1000)

xs = np.linspace(1e-10, np.max(samples), 200)

sns.distplot(samples, norm_hist=True, kde=False)

plt.plot(xs, log_normal.prob(xs), c='k', alpha=.75)

plt.show()

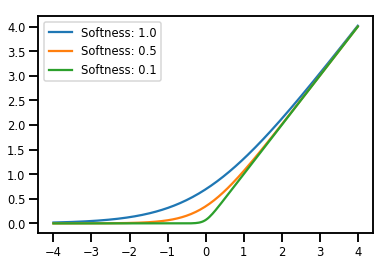

batching Bijectors

# Create a batch of bijectors of shape [3,]

softplus = tfp.bijectors.Softplus(

hinge_softness=[1., .5, .1])

print("Hinge softness shape:", softplus.hinge_softness.shape)

Hinge softness shape: (3,)

# For broadcasting, we want this to be shape [200, 1]

xs = np.linspace(-4., 4., 200)[..., np.newaxis]

ys = softplus.forward(xs)

print("Forward shape:", ys.shape)

Forward shape: (200, 3)

# Visualization

lines = plt.plot(np.tile(xs, 3), ys)

for line, hs in zip(lines, softplus.hinge_softness):

line.set_label("Softness: %1.1f" % hs)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Cache

# This bijector represents a matrix outer product on the forward pass,

# and a cholesky decomposition on the inverse pass. The latter costs O(N^3)!

bij = tfb.CholeskyOuterProduct()

size = 2500

# Make a big, lower-triangular matrix

big_lower_triangular = tf.eye(size)

# Squaring it gives us a positive-definite matrix

big_positive_definite = bij.forward(big_lower_triangular)

# Caching for the win!

%timeit bij.inverse(big_positive_definite)

%timeit tf.linalg.cholesky(big_positive_definite)

10000 loops, best of 3: 114 µs per loop 1 loops, best of 3: 208 ms per loop

MCMC

A TFP tem suporte integrado para alguns algoritmos Monte Carlo de cadeia de Markov padrão, incluindo Monte Carlo Hamiltoniano.

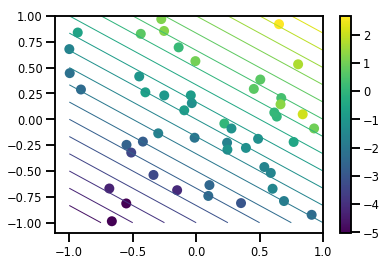

Gere um conjunto de dados

# Generate some data

def f(x, w):

# Pad x with 1's so we can add bias via matmul

x = tf.pad(x, [[1, 0], [0, 0]], constant_values=1)

linop = tf.linalg.LinearOperatorFullMatrix(w[..., np.newaxis])

result = linop.matmul(x, adjoint=True)

return result[..., 0, :]

num_features = 2

num_examples = 50

noise_scale = .5

true_w = np.array([-1., 2., 3.])

xs = np.random.uniform(-1., 1., [num_features, num_examples])

ys = f(xs, true_w) + np.random.normal(0., noise_scale, size=num_examples)

# Visualize the data set

plt.scatter(*xs, c=ys, s=100, linewidths=0)

grid = np.meshgrid(*([np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)] * 2))

xs_grid = np.stack(grid, axis=0)

fs_grid = f(xs_grid.reshape([num_features, -1]), true_w)

fs_grid = np.reshape(fs_grid, [100, 100])

plt.colorbar()

plt.contour(xs_grid[0, ...], xs_grid[1, ...], fs_grid, 20, linewidths=1)

plt.show()

Defina nossa função log-prob conjunta

A posterior não normalizada é o resultado de fecho sobre os dados para formar uma aplicação parcial do registo prov conjunta.

# Define the joint_log_prob function, and our unnormalized posterior.

def joint_log_prob(w, x, y):

# Our model in maths is

# w ~ MVN([0, 0, 0], diag([1, 1, 1]))

# y_i ~ Normal(w @ x_i, noise_scale), i=1..N

rv_w = tfd.MultivariateNormalDiag(

loc=np.zeros(num_features + 1),

scale_diag=np.ones(num_features + 1))

rv_y = tfd.Normal(f(x, w), noise_scale)

return (rv_w.log_prob(w) +

tf.reduce_sum(rv_y.log_prob(y), axis=-1))

# Create our unnormalized target density by currying x and y from the joint.

def unnormalized_posterior(w):

return joint_log_prob(w, xs, ys)

Construir HMC TransitionKernel e chamar sample_chain

# Create an HMC TransitionKernel

hmc_kernel = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=unnormalized_posterior,

step_size=np.float64(.1),

num_leapfrog_steps=2)

# We wrap sample_chain in tf.function, telling TF to precompile a reusable

# computation graph, which will dramatically improve performance.

@tf.function

def run_chain(initial_state, num_results=1000, num_burnin_steps=500):

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_results,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=initial_state,

kernel=hmc_kernel,

trace_fn=lambda current_state, kernel_results: kernel_results)

initial_state = np.zeros(num_features + 1)

samples, kernel_results = run_chain(initial_state)

print("Acceptance rate:", kernel_results.is_accepted.numpy().mean())

Acceptance rate: 0.915

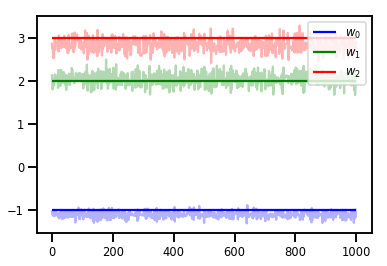

Isso não é ótimo! Gostaríamos de uma taxa de aceitação próxima de 0,65.

(ver "Optimal Scaling para vários Metropolis-Hastings Algoritmos" , Roberts & Rosenthal, 2001)

Tamanhos de etapas adaptáveis

Nós podemos envolver nosso HMC TransitionKernel em um SimpleStepSizeAdaptation "meta-kernel", que irá aplicar alguma lógica (bastante simples heurística) para adaptar o tamanho do passo HMC durante queimando. Alocamos 80% do burnin para adaptar o tamanho do passo e, em seguida, deixamos os 20% restantes irem apenas para a mistura.

# Apply a simple step size adaptation during burnin

@tf.function

def run_chain(initial_state, num_results=1000, num_burnin_steps=500):

adaptive_kernel = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

hmc_kernel,

num_adaptation_steps=int(.8 * num_burnin_steps),

target_accept_prob=np.float64(.65))

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_results,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=initial_state,

kernel=adaptive_kernel,

trace_fn=lambda cs, kr: kr)

samples, kernel_results = run_chain(

initial_state=np.zeros(num_features+1))

print("Acceptance rate:", kernel_results.inner_results.is_accepted.numpy().mean())

Acceptance rate: 0.634

# Trace plots

colors = ['b', 'g', 'r']

for i in range(3):

plt.plot(samples[:, i], c=colors[i], alpha=.3)

plt.hlines(true_w[i], 0, 1000, zorder=4, color=colors[i], label="$w_{}$".format(i))

plt.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.show()

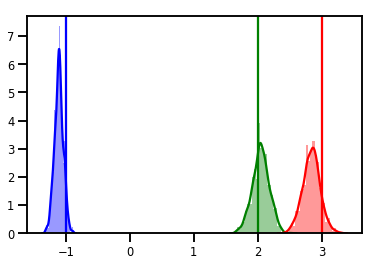

# Histogram of samples

for i in range(3):

sns.distplot(samples[:, i], color=colors[i])

ymax = plt.ylim()[1]

for i in range(3):

plt.vlines(true_w[i], 0, ymax, color=colors[i])

plt.ylim(0, ymax)

plt.show()

Diagnóstico

Os traços são bons, mas os diagnósticos são melhores!

Primeiro, precisamos executar várias cadeias. Isto é tão simples como dar um lote de initial_state tensores.

# Instead of a single set of initial w's, we create a batch of 8.

num_chains = 8

initial_state = np.zeros([num_chains, num_features + 1])

chains, kernel_results = run_chain(initial_state)

r_hat = tfp.mcmc.potential_scale_reduction(chains)

print("Acceptance rate:", kernel_results.inner_results.is_accepted.numpy().mean())

print("R-hat diagnostic (per latent variable):", r_hat.numpy())

Acceptance rate: 0.59175 R-hat diagnostic (per latent variable): [0.99998395 0.99932185 0.9997064 ]

Amostragem da escala de ruído

# Define the joint_log_prob function, and our unnormalized posterior.

def joint_log_prob(w, sigma, x, y):

# Our model in maths is

# w ~ MVN([0, 0, 0], diag([1, 1, 1]))

# y_i ~ Normal(w @ x_i, noise_scale), i=1..N

rv_w = tfd.MultivariateNormalDiag(

loc=np.zeros(num_features + 1),

scale_diag=np.ones(num_features + 1))

rv_sigma = tfd.LogNormal(np.float64(1.), np.float64(5.))

rv_y = tfd.Normal(f(x, w), sigma[..., np.newaxis])

return (rv_w.log_prob(w) +

rv_sigma.log_prob(sigma) +

tf.reduce_sum(rv_y.log_prob(y), axis=-1))

# Create our unnormalized target density by currying x and y from the joint.

def unnormalized_posterior(w, sigma):

return joint_log_prob(w, sigma, xs, ys)

# Create an HMC TransitionKernel

hmc_kernel = tfp.mcmc.HamiltonianMonteCarlo(

target_log_prob_fn=unnormalized_posterior,

step_size=np.float64(.1),

num_leapfrog_steps=4)

# Create a TransformedTransitionKernl

transformed_kernel = tfp.mcmc.TransformedTransitionKernel(

inner_kernel=hmc_kernel,

bijector=[tfb.Identity(), # w

tfb.Invert(tfb.Softplus())]) # sigma

# Apply a simple step size adaptation during burnin

@tf.function

def run_chain(initial_state, num_results=1000, num_burnin_steps=500):

adaptive_kernel = tfp.mcmc.SimpleStepSizeAdaptation(

transformed_kernel,

num_adaptation_steps=int(.8 * num_burnin_steps),

target_accept_prob=np.float64(.75))

return tfp.mcmc.sample_chain(

num_results=num_results,

num_burnin_steps=num_burnin_steps,

current_state=initial_state,

kernel=adaptive_kernel,

seed=(0, 1),

trace_fn=lambda cs, kr: kr)

# Instead of a single set of initial w's, we create a batch of 8.

num_chains = 8

initial_state = [np.zeros([num_chains, num_features + 1]),

.54 * np.ones([num_chains], dtype=np.float64)]

chains, kernel_results = run_chain(initial_state)

r_hat = tfp.mcmc.potential_scale_reduction(chains)

print("Acceptance rate:", kernel_results.inner_results.inner_results.is_accepted.numpy().mean())

print("R-hat diagnostic (per w variable):", r_hat[0].numpy())

print("R-hat diagnostic (sigma):", r_hat[1].numpy())

Acceptance rate: 0.715875 R-hat diagnostic (per w variable): [1.0000073 1.00458208 1.00450512] R-hat diagnostic (sigma): 1.0092056996149859

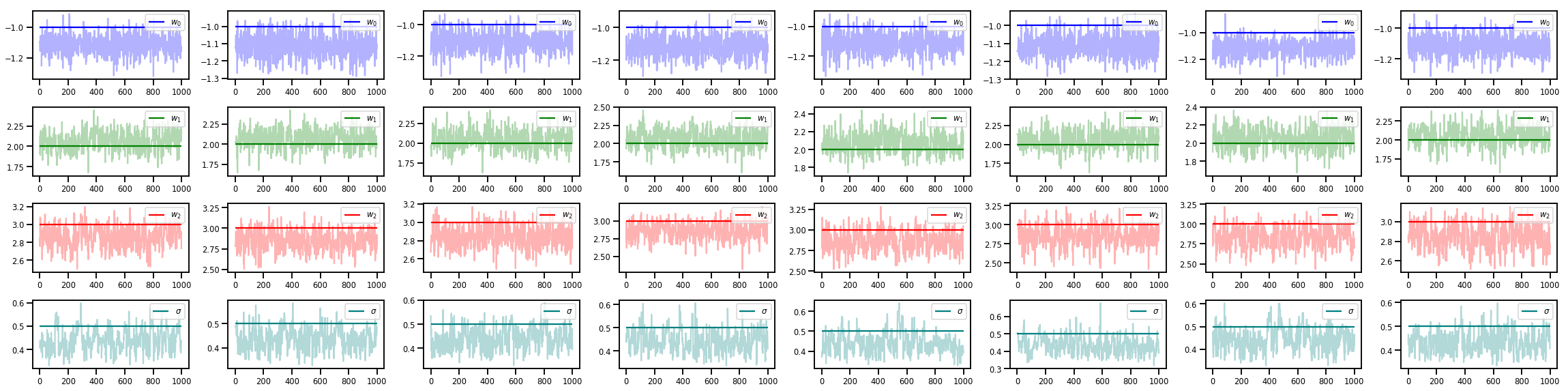

w_chains, sigma_chains = chains

# Trace plots of w (one of 8 chains)

colors = ['b', 'g', 'r', 'teal']

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4, num_chains, figsize=(4 * num_chains, 8))

for j in range(num_chains):

for i in range(3):

ax = axes[i][j]

ax.plot(w_chains[:, j, i], c=colors[i], alpha=.3)

ax.hlines(true_w[i], 0, 1000, zorder=4, color=colors[i], label="$w_{}$".format(i))

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

ax = axes[3][j]

ax.plot(sigma_chains[:, j], alpha=.3, c=colors[3])

ax.hlines(noise_scale, 0, 1000, zorder=4, color=colors[3], label=r"$\sigma$".format(i))

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

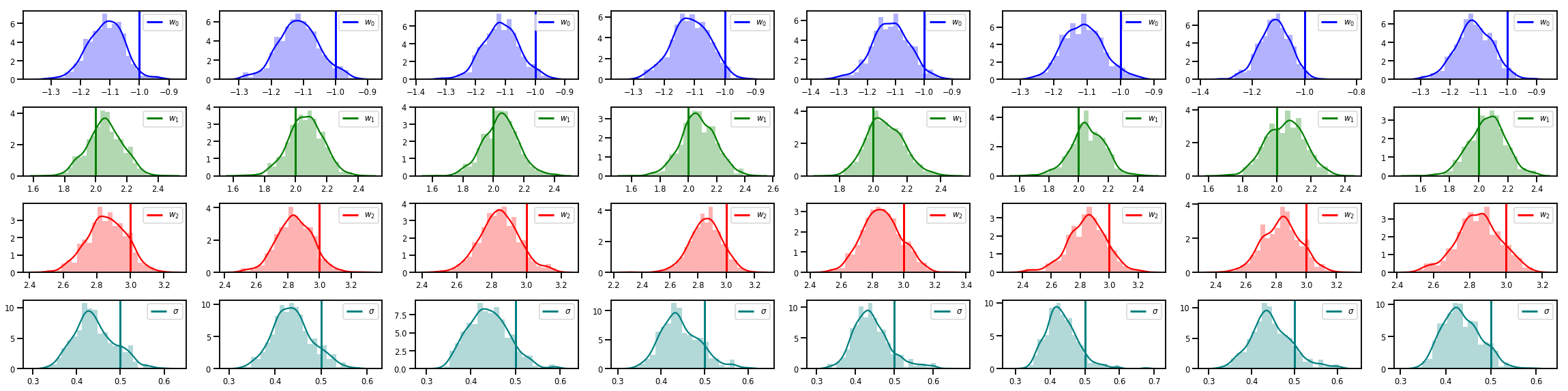

# Histogram of samples of w

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4, num_chains, figsize=(4 * num_chains, 8))

for j in range(num_chains):

for i in range(3):

ax = axes[i][j]

sns.distplot(w_chains[:, j, i], color=colors[i], norm_hist=True, ax=ax, hist_kws={'alpha': .3})

for i in range(3):

ax = axes[i][j]

ymax = ax.get_ylim()[1]

ax.vlines(true_w[i], 0, ymax, color=colors[i], label="$w_{}$".format(i), linewidth=3)

ax.set_ylim(0, ymax)

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

ax = axes[3][j]

sns.distplot(sigma_chains[:, j], color=colors[3], norm_hist=True, ax=ax, hist_kws={'alpha': .3})

ymax = ax.get_ylim()[1]

ax.vlines(noise_scale, 0, ymax, color=colors[3], label=r"$\sigma$".format(i), linewidth=3)

ax.set_ylim(0, ymax)

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Tem muito mais!

Confira estas postagens de blog e exemplos legais:

- Structural Time Series apoio blogue colab

- Camadas probabilística Keras (entrada: Tensor, saída: Distribuição!) Blogue colab

- Gaussian Processo de Regressão colab e variável latente Modeling colab

Mais exemplos e notebooks em nosso GitHub aqui !